Various addresses on South and Fulton Streets

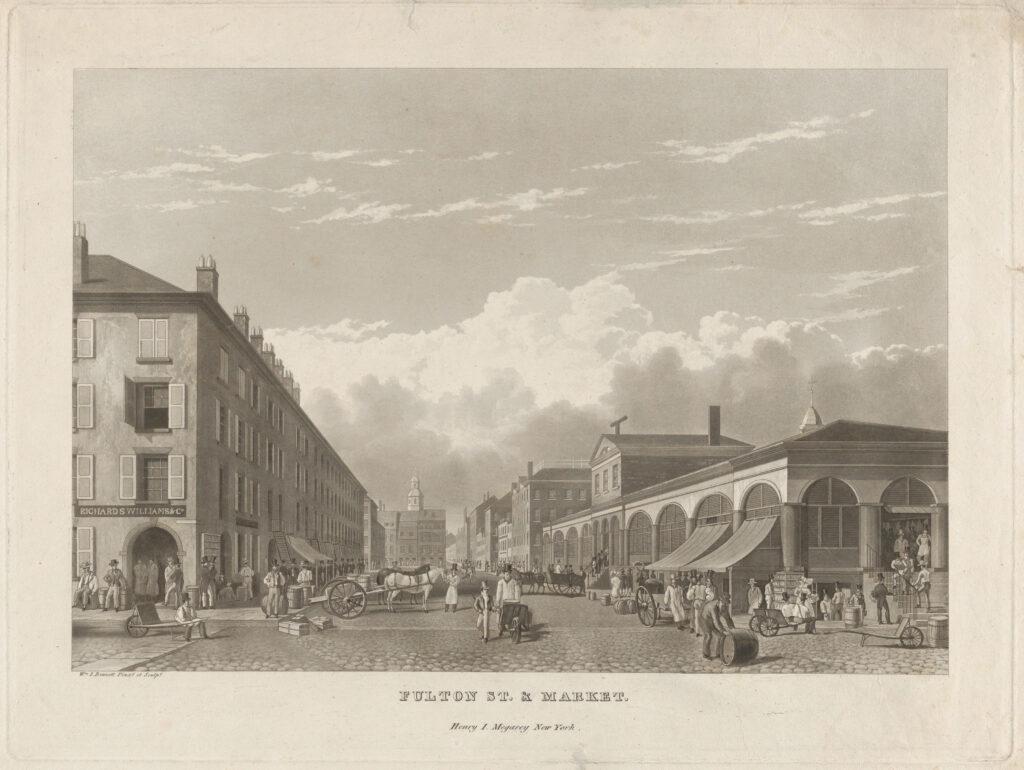

Built as a real estate investment for captain, shipchandler, and merchant Peter Schermerhorn (1749–1826), Schermerhorn Row was designed with the bustling 19th century East River waterfront in mind. Each address in this block of buildings offered a storefront, an office, and ample warehouse space on upper floors for the goods flowing into the port city. The Row’s location proved excellent for business; the Fulton Ferry conveniently connected Manhattan to Brooklyn in 1814 and the Fulton Market opened across the street in 1822.

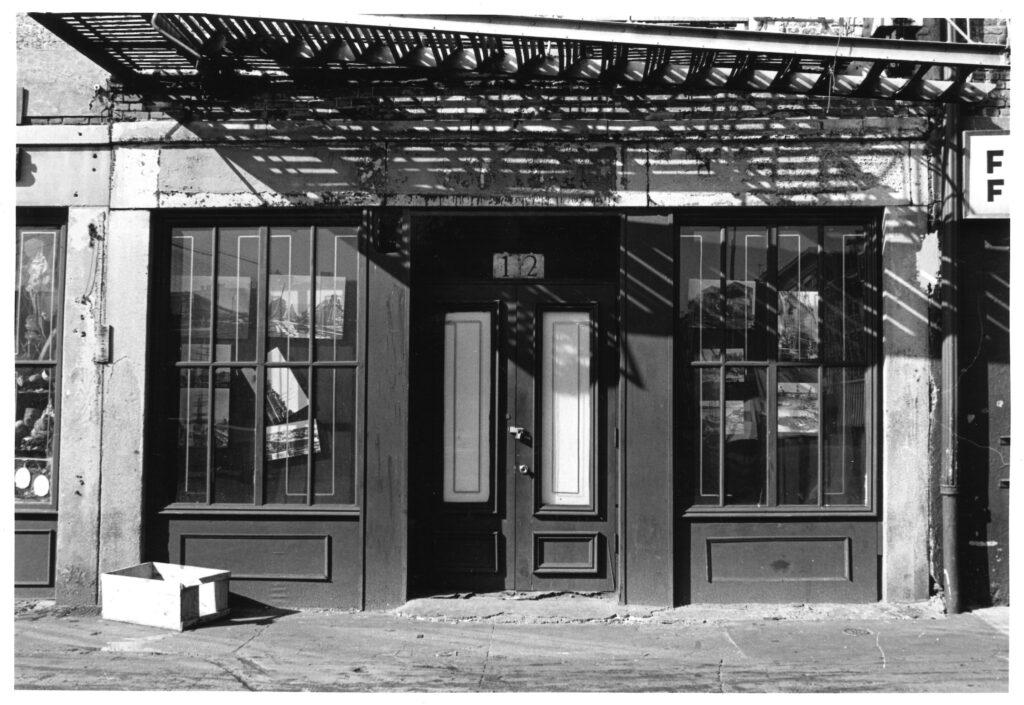

Today, Schermerhorn Row is part of the South Street Seaport Museum and holds two galleries on the first floor that give an introduction to the history of New York and its growth as a port city. Located at 12 Fulton Street, the first-floor galleries are open to the public as part of Museum admission. The upper floors galleries are currently administrative space for the Museum and include the Remains of the Old Hotels. The Museum is currently engaged in a number of campus capital projects that will restore, interpret, and reopen these spaces for future visitors.

The First World Trade Center

Built during a period of great enthusiasm for expanding the city, the entirety of Schermerhorn Row took only two years to complete. The man behind the largest commercial building project in New York at the time was Peter John Schermerhorn (1749–1826). He was a captain, merchant, investor, and real-estate developer eager to take advantage of the trade boom on South Street at the time.

The completion of Schermerhorn Row could not have come at a more opportune time. By 1797, New York had become the largest port in the United States.

The ten-year period from 1815 to 1825—from when the War of 1812 ended, to when the Erie Canal was completed—represented a boom time for commerce, solidifying New York’s position as the main port of the nation.

The buildings of Schermerhorn Row were at the crossroads of international and domestic trade, immigration (prior to the opening of Castle Garden in 1855), and the commuting population of a growing city.

“Fulton Street, 1821” by Sarah Pierson (active approximately 1821). Graphic reproduction courtesy of The Frick Art Reference Library.

Schermerhorn Row helped usher in a new age in commercial architecture that was built solely for commerce, in what was then known as a counting-house. It combined storefronts, offices, and warehouses into one building. Each floor was connected with a special hoistway to move goods efficiently from one floor to another. Upon completion, Schermerhorn Row quickly filled with merchant tenants. With so many traders working in close proximity, the Row’s convenient location near the piers, and its cutting-edge design for the rapid processing of cargo, Schermerhorn Row quickly became the commercial heart of South Street. It was New York’s first world trade center.

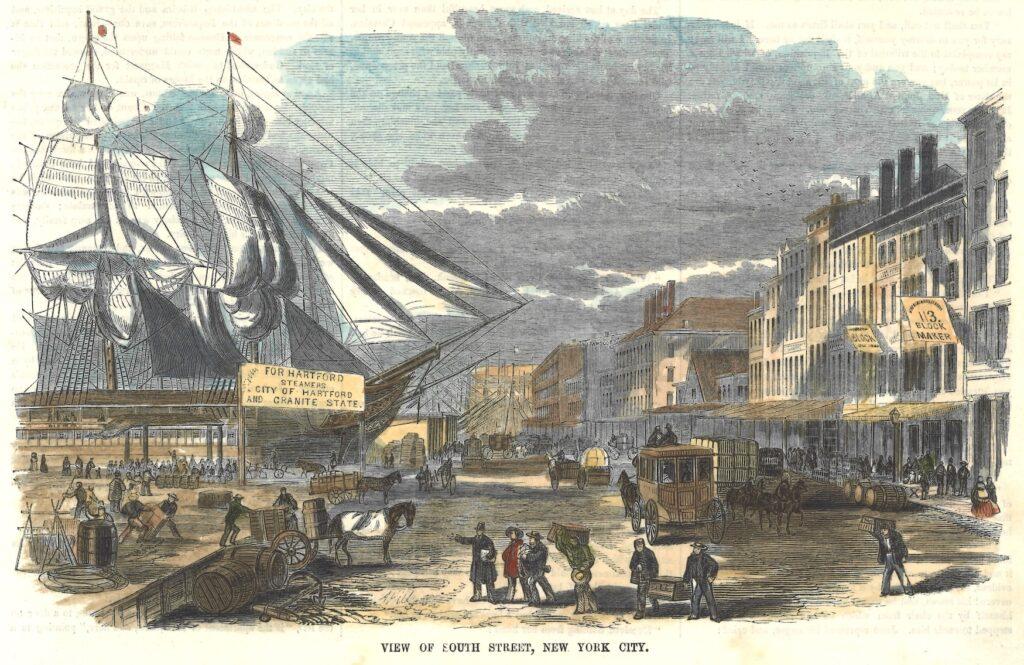

Detail from “View of South Street, New York City” March 7, 1857. Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, publisher. Newspaper Illustration Collection, 2005.003.0008

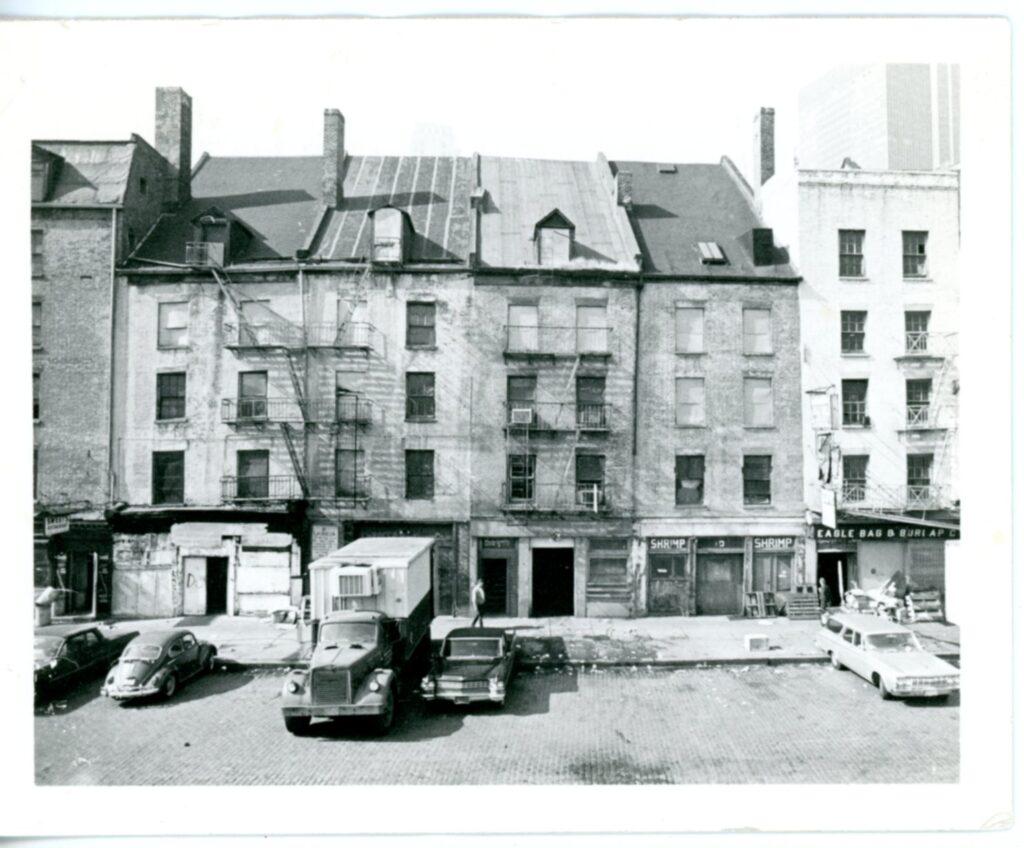

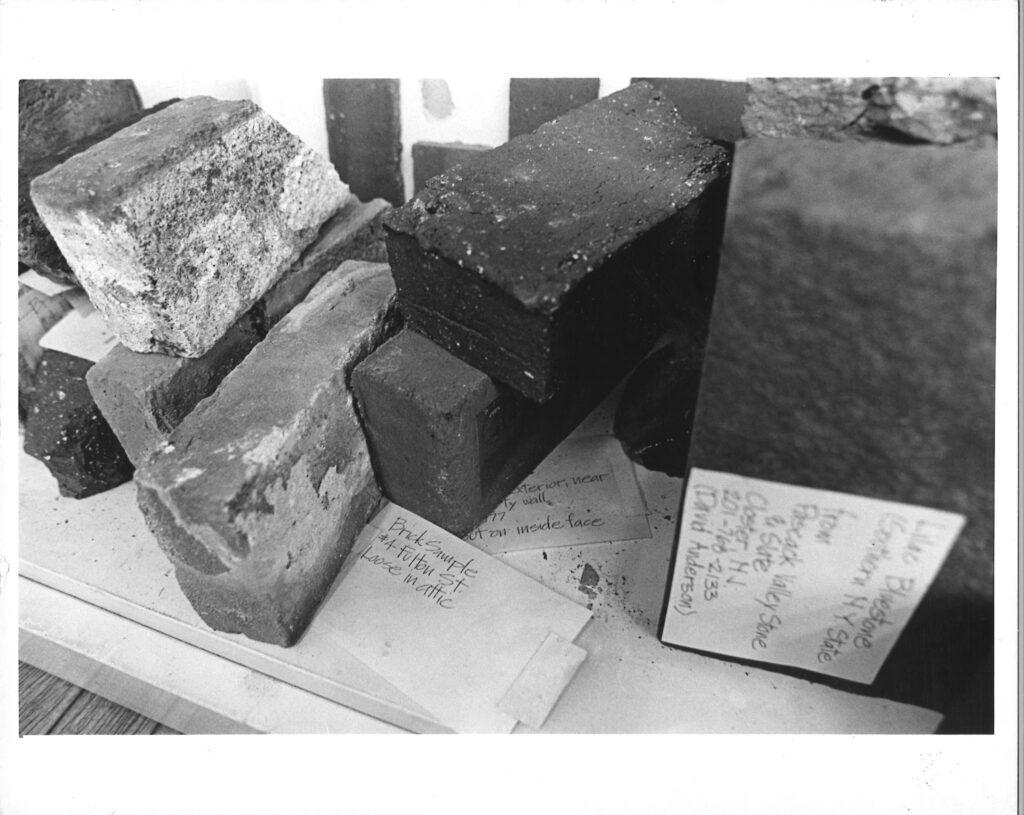

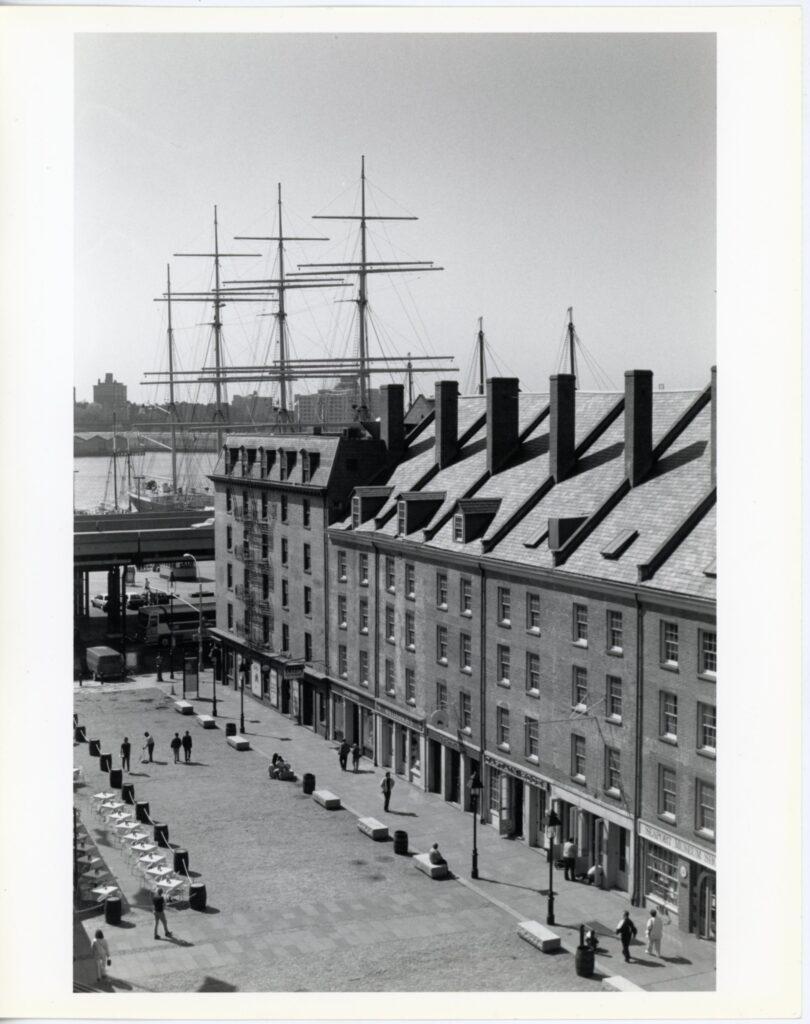

The façades boast one of New York City’s best surviving examples of Georgian-Federal style architecture. The structures were originally made of soft, hand-molded bricks, with upper stories featuring double-hung windows with splayed stone lintels. Modifications to the original structure are visible along the steeply-pitched roofs, including the addition of dormer windows—visible today from Fulton Street—and the construction of party walls designed to prevent fires from spreading across rooftops.

Even though these tall, handsome stores seem more conveniently located and more spacious than the building the Schermerhorn chandlery occupied at 243 Water Street, the new Row was intended as an income source and was never occupied by the family firm. All stores were leased to other merchants. However, in 1812, and again from 1815 through 1817, John Peter Schermerhorn (1775–1831)—a son of Peter the elder who had not joined the original firm—operated his own ship chandlery from the Row, first at 12 Fulton Street, then in No. 14[1]Walking Around South Street by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock, 1974, pp. 8-11..

Seaport Changes

By the late 1840s, many of the old street-level brick fronts had been replaced by the granite-piered storefronts that were popular in the Greek Revival style, and after another ten years were altered to include cast-iron columns. Today, all of the Row’s ground floors have been modified several times throughout the ceaseless commercial flux they endured over the centuries. However, the façade of the upper floors remain mostly as it was constructed, with the exceptions of a few alterations in window size, two changes to the roof, and the removal of most of the chimneys. Nearly all of the earliest tenants in the Row were classified as “merchants,” but later occupants had varied trades such as grocers, provisioners, eating houses, hotels, liquor shops, taverns, clothiers, clerks, bootmakers, barbers, and even a “factory” later occupied the buildings. Many of these tenants made changes to the Row to suit their own needs.

Remains of the Old Hotels inside Schermerhorn Row

Starting in the 1850s, Schermerhorn Row’s buildings were converted into a series of hotels, and today the remains of some of these rooms and walls are preserved and cared for by the Seaport Museum as part of its special collections[2]Learn more about the history and care of these historical remnants in the Collections Chronicles blog post “Housekeeping in a 150 year old Hotel.”. These remains are a testimony to the changing fortunes of the building, and the rapid evolution of the seaport during the 19th and 20th centuries, from the trade in commodities to lodgers.

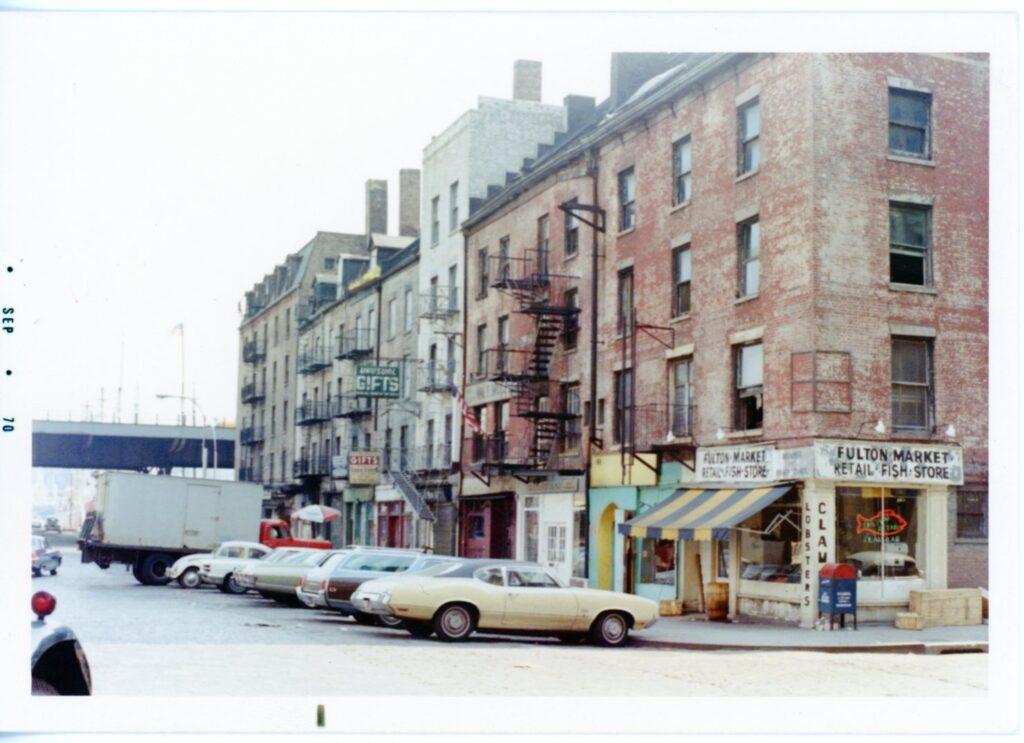

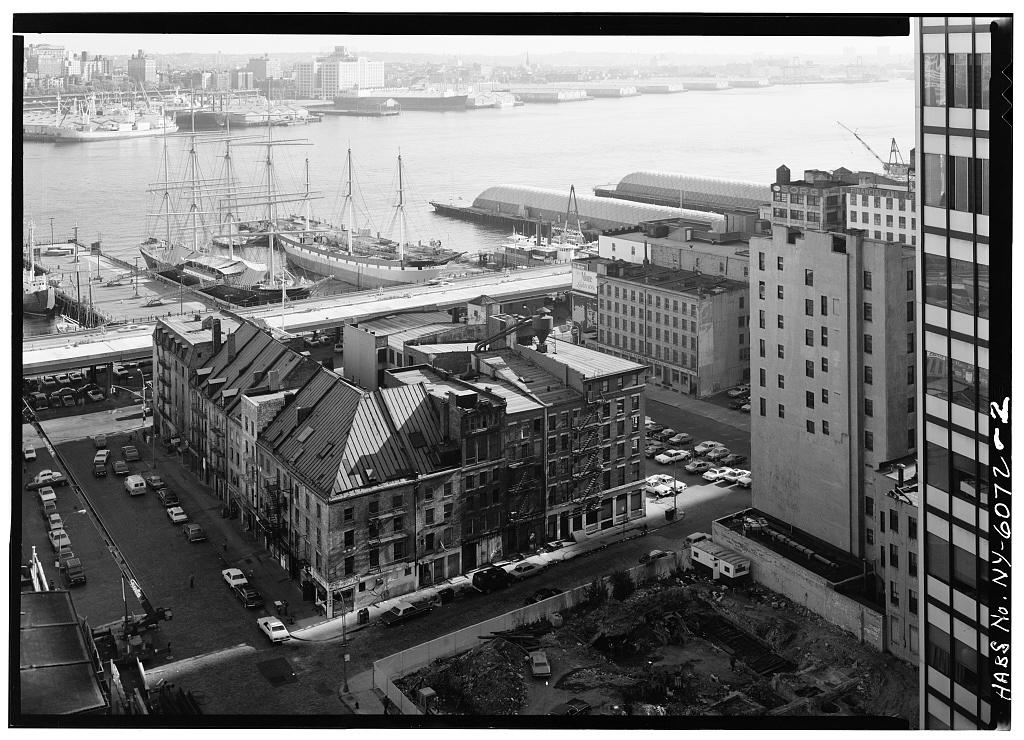

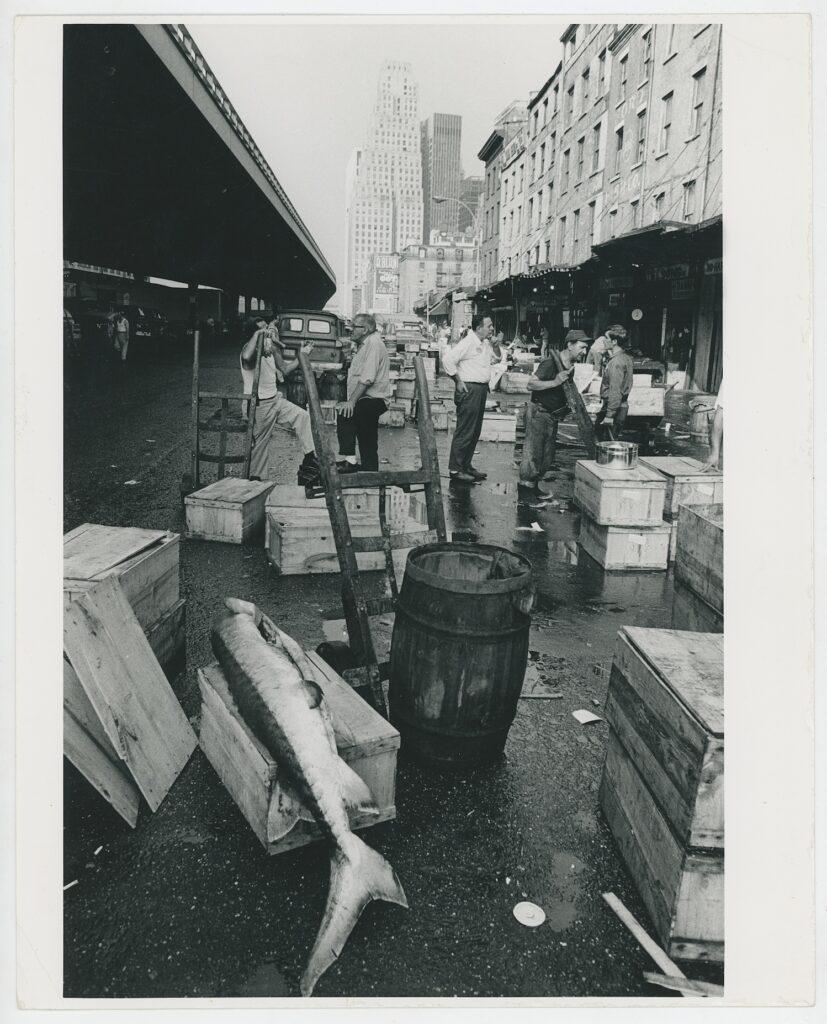

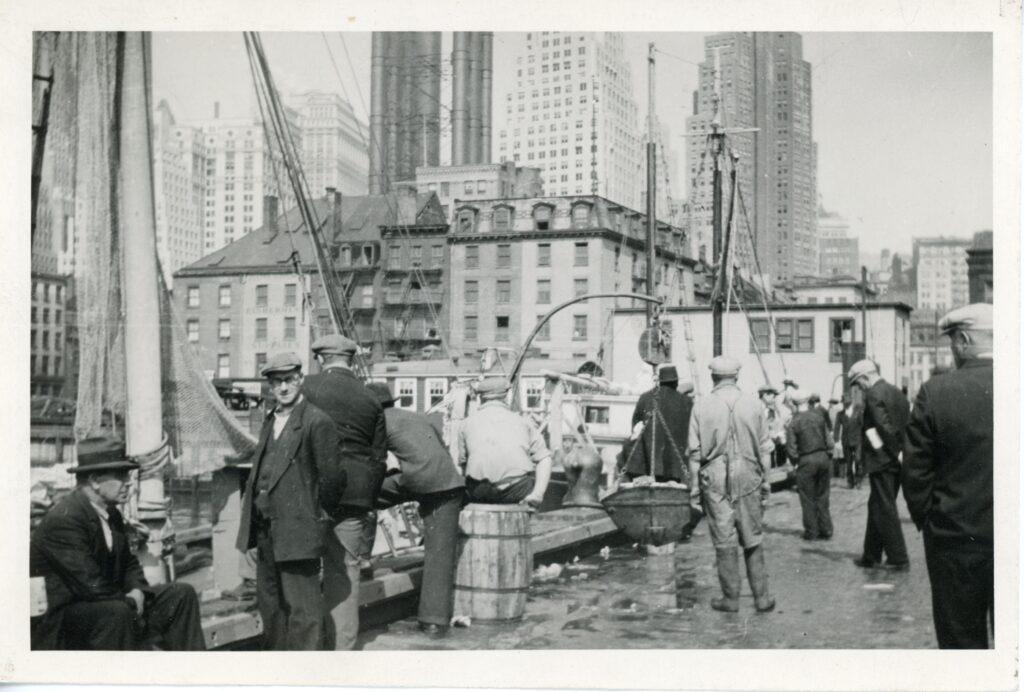

Towards the end of the 19th century, South Street became a victim of its own success. The continued increase in the volume of shipping traffic and size of steamships was too much for the old seaport to handle alone. The Hudson River waterfront became the city’s new maritime trading hub, and the East River commuter ferries struggled to compete with the Brooklyn Bridge after it opened in 1883. With reduced commercial activity (except for the famous wholesale Fulton Fish Market) and travelers in the area, Schermerhorn Row entered a period of decline.

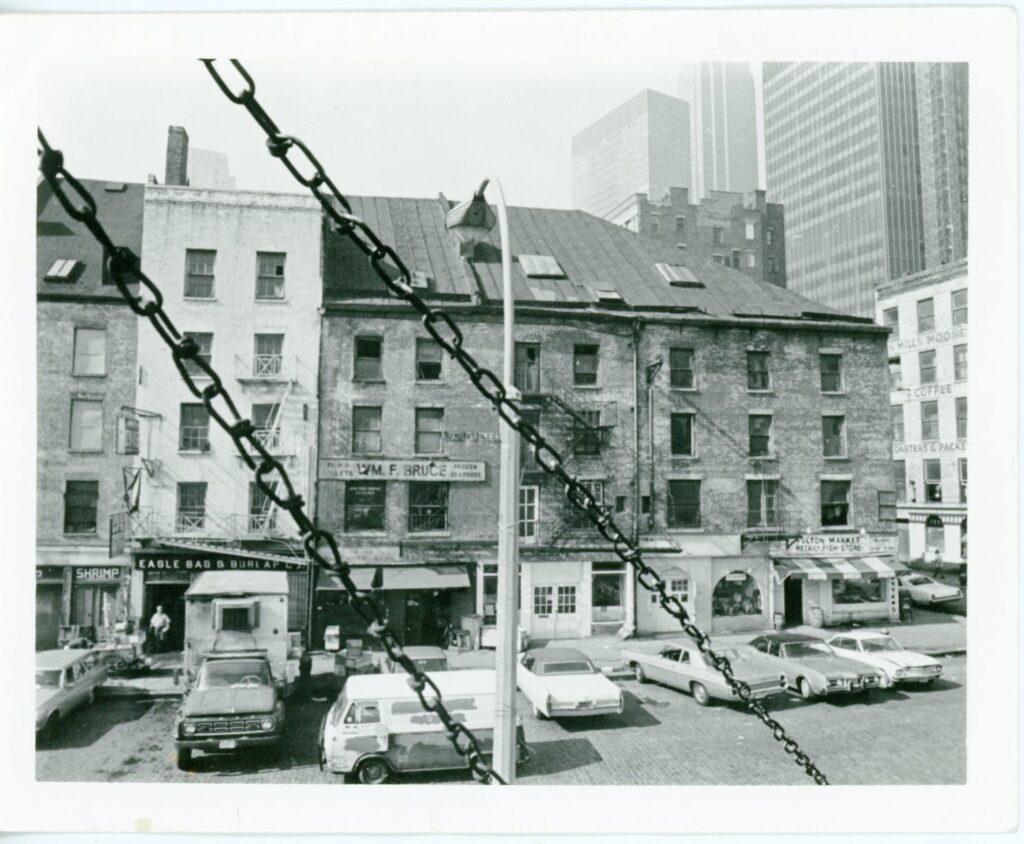

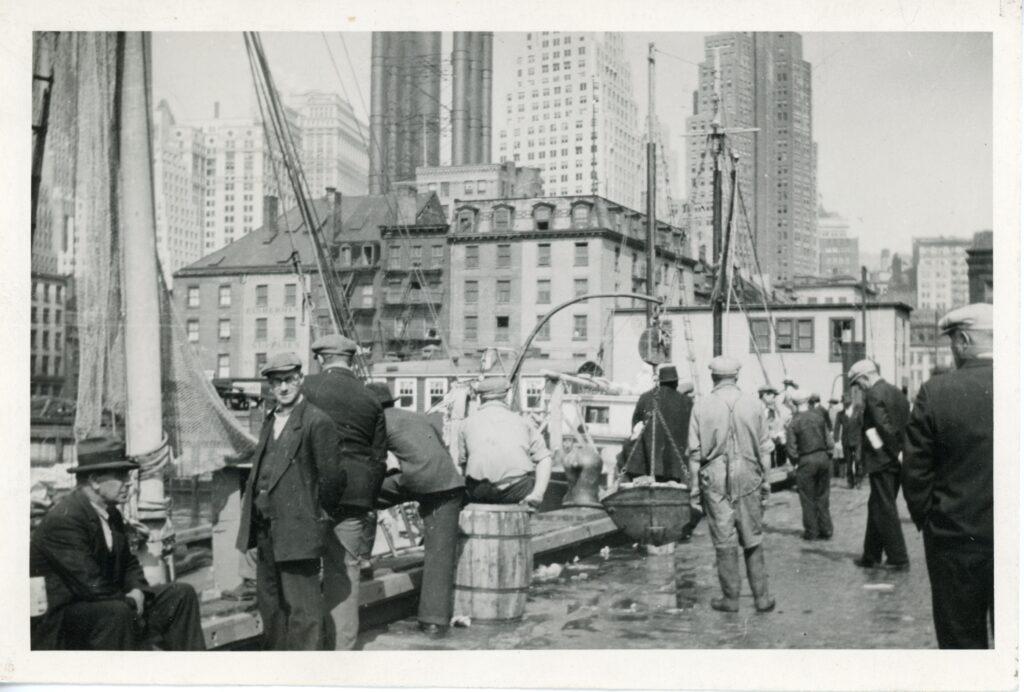

Left: “Fulton Fish Market Slip” n.d. (original 1940). South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive, H21-0016

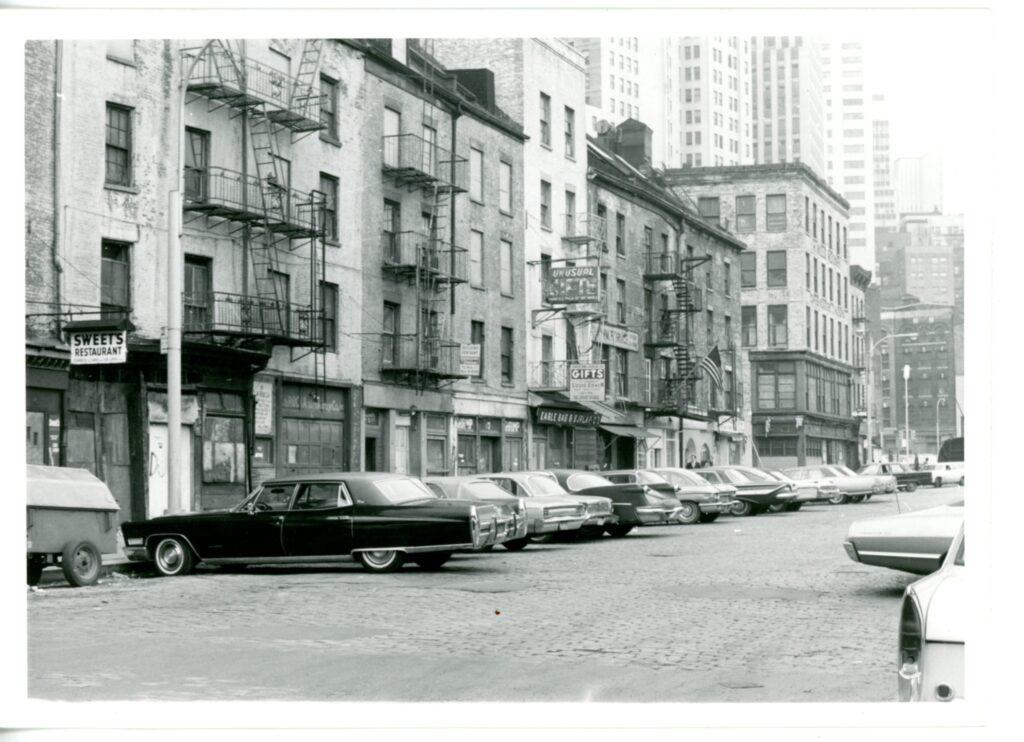

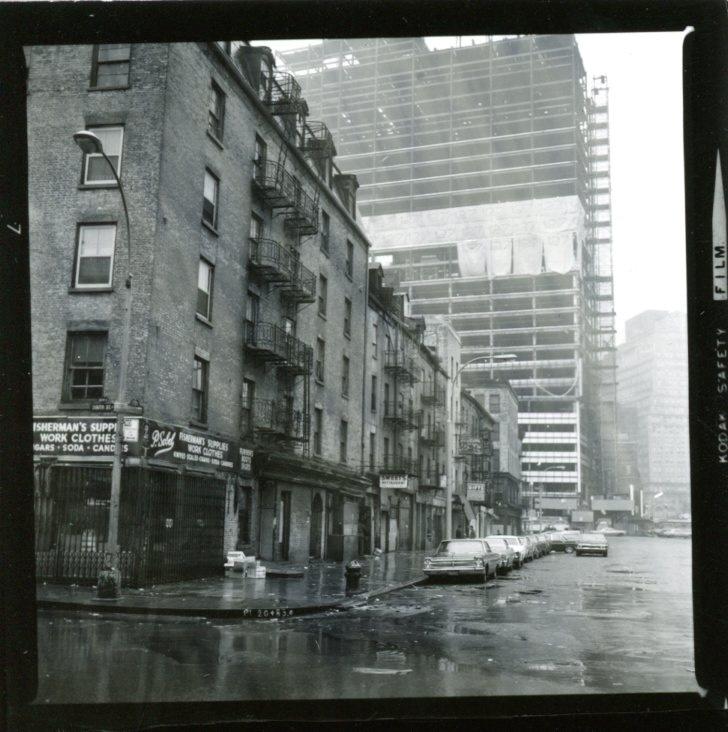

Right: “Schermerhorn Row” ca. 1960. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive

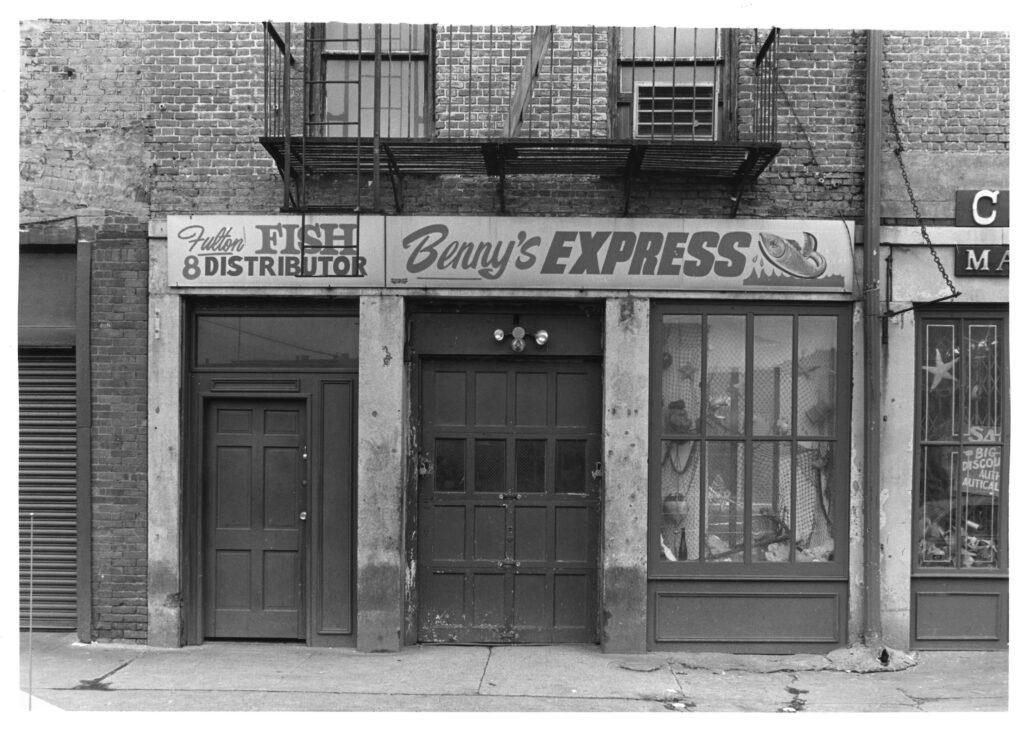

Many fish distributors and processors gained occupancy in the Row in the second quarter of the 20th century, causing major impacts on the building interiors, as well as on the character of Fulton Street. Remaining floor-framing systems and ground-floor architectural fabric from previous shops or restaurants were removed to make space for cement floors and refrigerators. Second floors were often converted into offices, and the upper floors were generally abandoned.

In 1941, A Maritime History of New York was compiled by the New York City Work Projects Administration (WPA) Writers Program. The book details the history of the Port of New York in a 400-year-saga, from its formation in the Ice Age to the US entry into World War II, honoring the unwavering spirit of its people, the resilience of the city, and the enduring allure of its bustling seaport.

Later, in 1952, Joseph Mitchell (1908–1996), a writer for The New Yorker and chronicler of everyday life in the city, first published Up the Old Hotel, a short story about adventuring with restaurant proprietor Louie Marino into the long-abandoned upper floors of Schermerhorn Row above Marino’s restaurant at 92 South Street, where they “rediscovered” the remains of the old hotels. These were the first indications that the seaport held a place of fascination in the public’s mind, and was an important part of the city’s heritage, worth remembering and understanding.

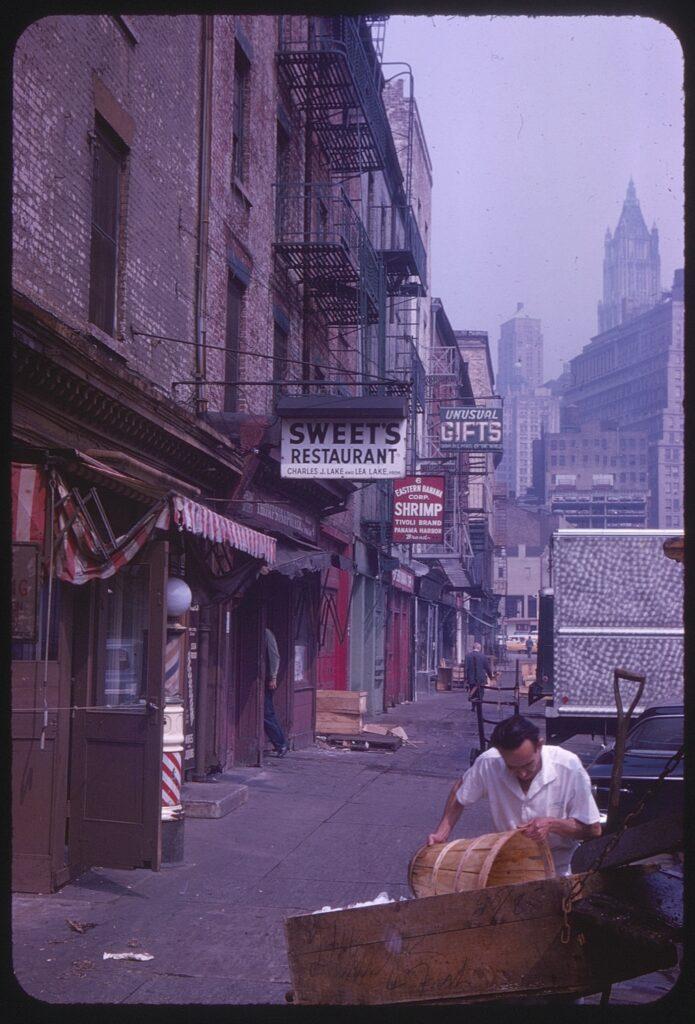

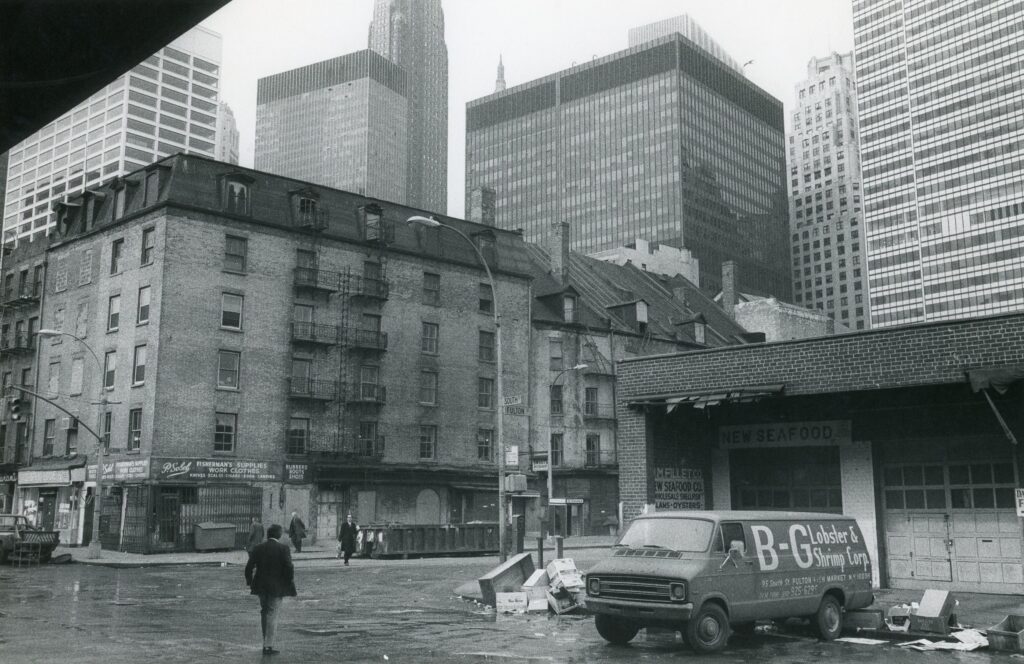

Left: “South Street”, June 6, 1963. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Right: “Schermerhorn Row”, July 1968. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Landmark and Preservation Efforts

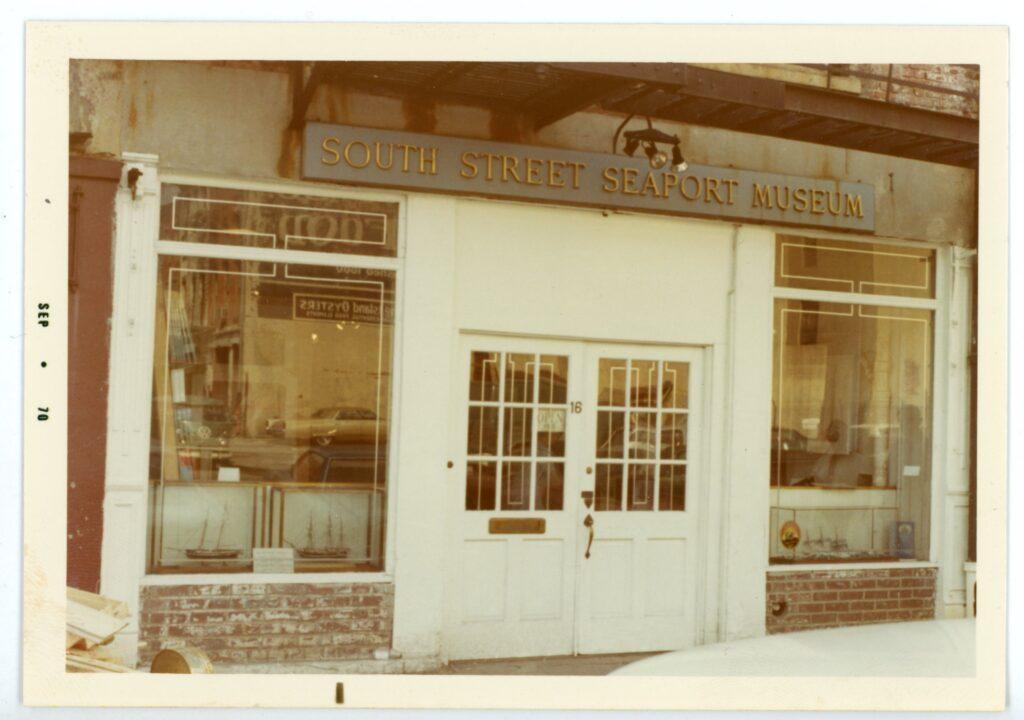

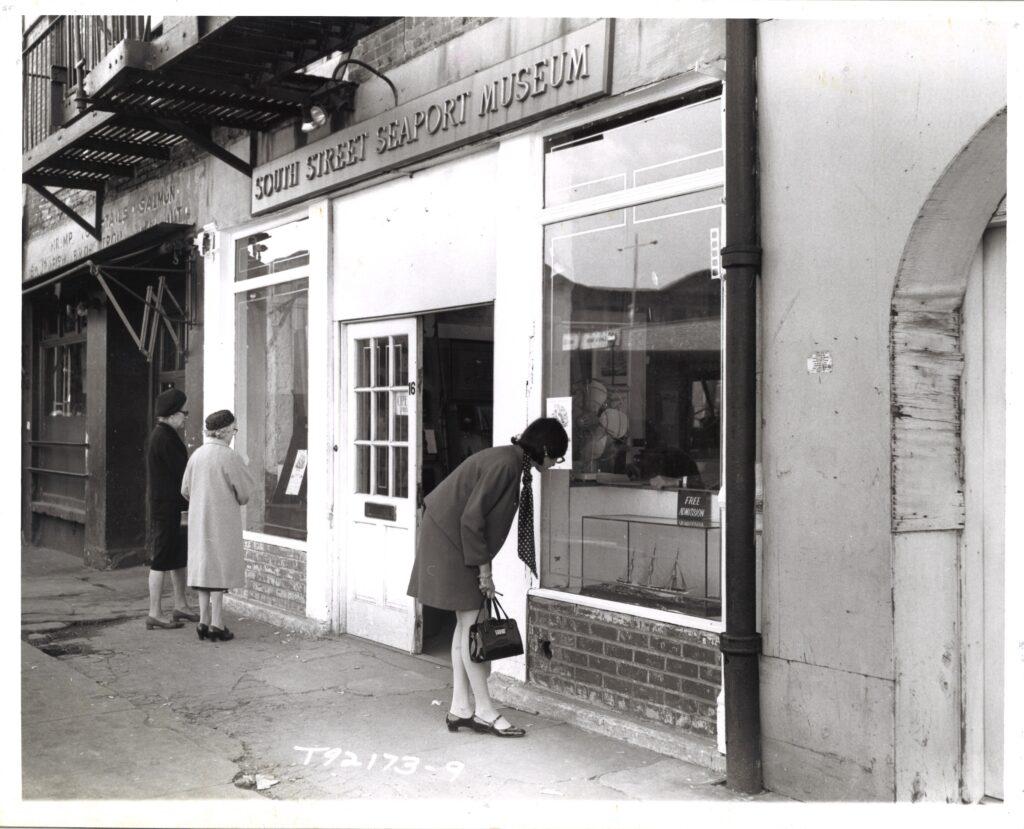

Interest in the seaport would peak again in the late 1960s, when it was threatened with demolition as part of urban renewal practices. Schermerhorn Row block reached a critical point, but was saved by the grassroots preservationists who would become the founders of the South Street Seaport Museum.

The 1960s was also a period when New Yorkers, like many Americans, were more acutely concerned with preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of their communities, as post-war development was rapidly, and drastically, changing landscapes. In New York, urban renewal was destroying entire neighborhoods and buildings of great significance, including the infamous destruction of Penn Station, which prompted the creation of the 1965 New York City Landmarks Law.

Between 1968 and 1970, a series of background papers, consultant reports, and preliminary Museum plans were written. In 1971, the Schermerhorn Row Block was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1972, the State Urban Development Corporation (UDC) began to assess the economic feasibility of developing the Block. UDC could accept the Block only if the buildings were vacant, and the artists living in Schermerhorn Row and Front Street at the time organized a tenants’ union to oppose their eviction. An agreement was reached the following year, in February of 1973[3]Creative Time was one of the organizations that emerged out of these conversations thanks to of an informal discussion between three friends: Karin Bacon and Susan Henshaw Jones, who worked in Mayor … Continue reading.

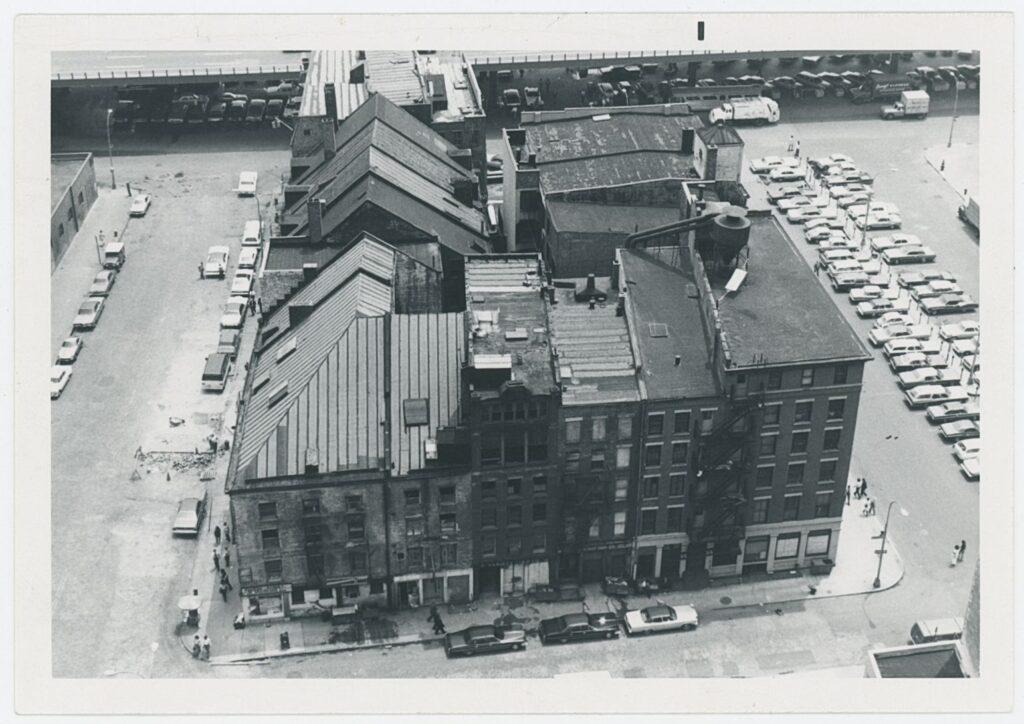

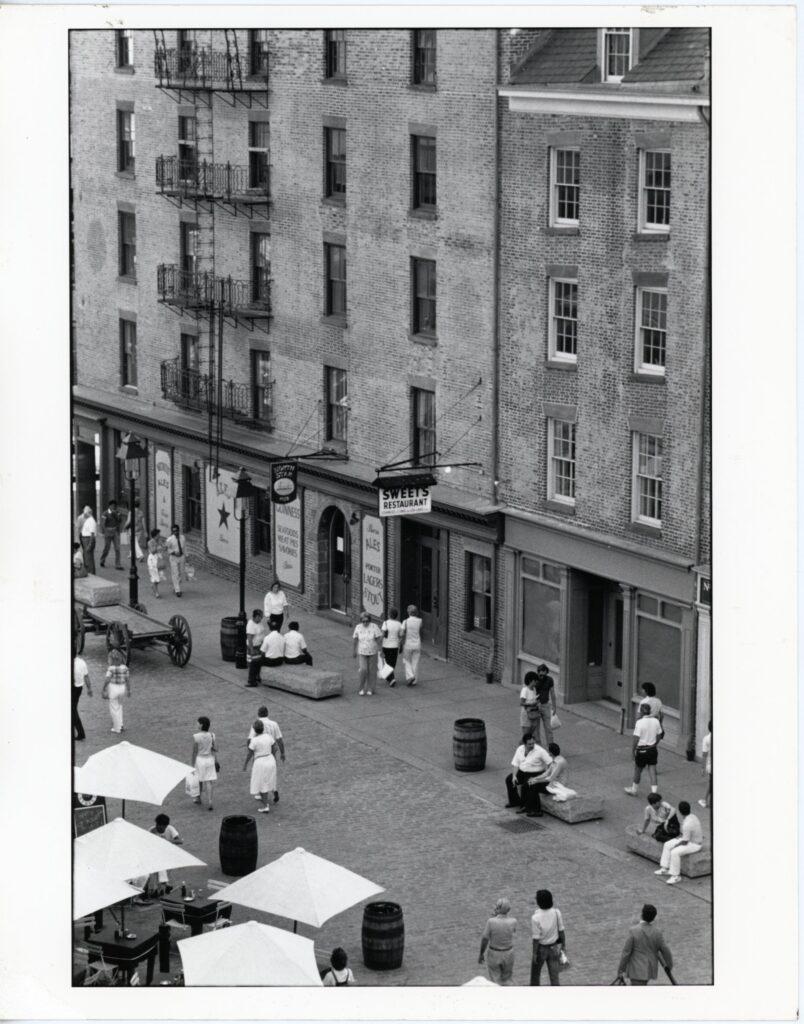

[Aerial view of Schermerhorn Row Block] ca. 1975. South Street Seaport Museum Photo Archive, H102-0589

As part of the historic preservation movement of this time, two parties became interested in preserving the intact early to mid-19th century buildings in the seaport, particularly the Schermerhorn Row Block. In 1966, the State of New York created the South Street Seaport Maritime Association with the intent to establish the New York State Maritime Museum (NYSMM), while in 1967 the community activist group Friends of the South Street Seaport organized and established the South Street Seaport Museum. Of these two parallel organizations, the Seaport Museum continues to operate today, while the NYSMM was dissolved in 1979.

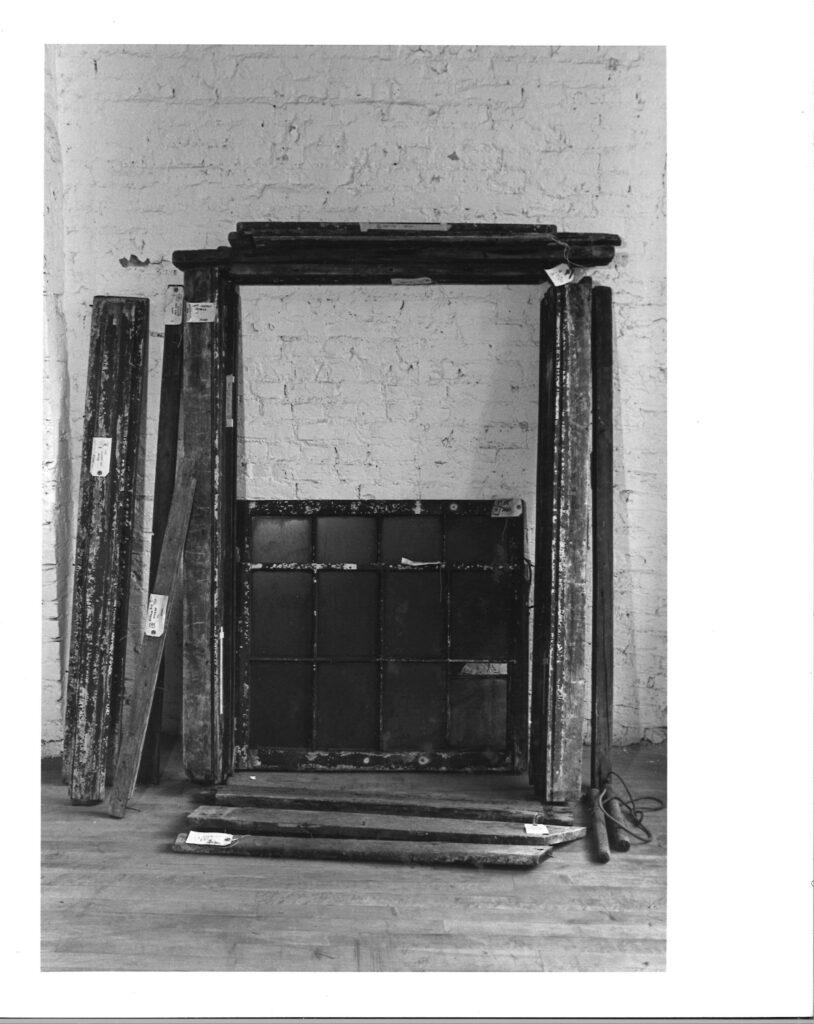

The buildings that compose the Row of counting houses were individually landmarked in 1976, and in 1977 the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation commissioned Jan Hird Pokorny Associates (JHPA) to provide a master plan and design documents for the restoration and adaptive reuse of the block.

Between 1977 and 1984, JHPA implemented the stabilization of the buildings, researched the reconstruction of missing historic elements, and installed extensive mechanical systems. The project received the prestigious Bard Award for excellence in design from the Municipal Arts Society.

“Dogherty Loading Zone (Schermerhorn Row)” 1982 (original negative), 2008 (print). Museum Purchase, 2008.005.0032

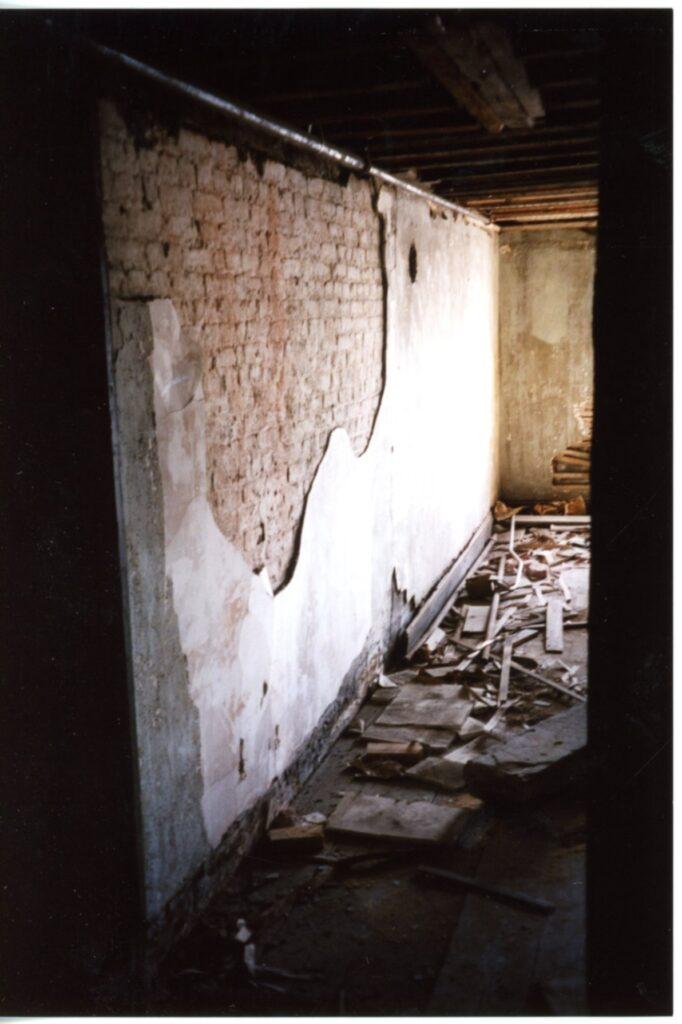

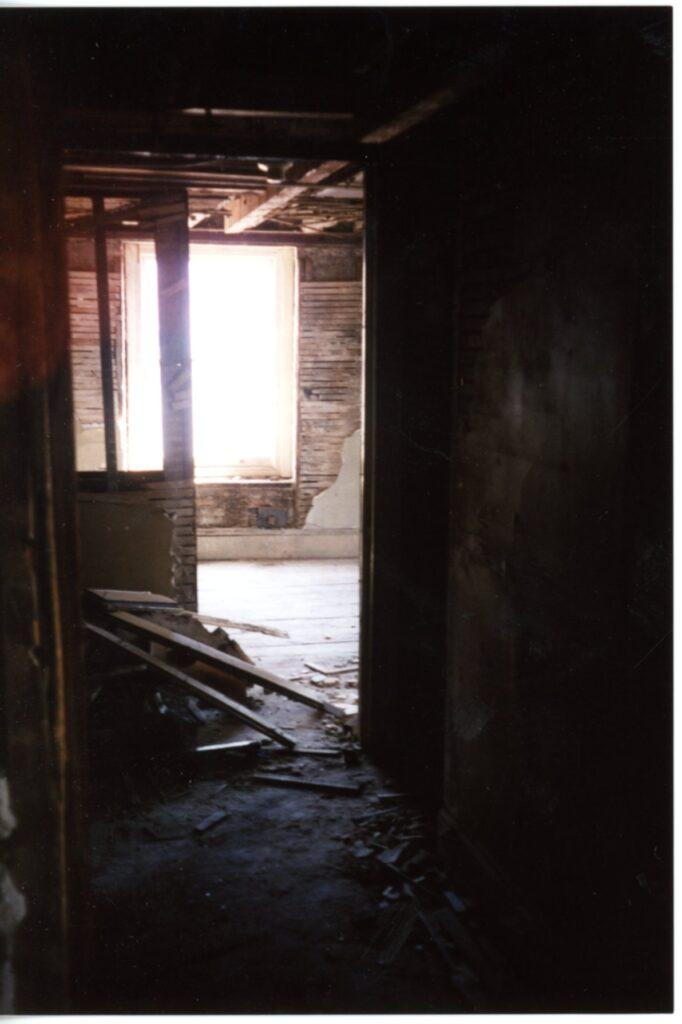

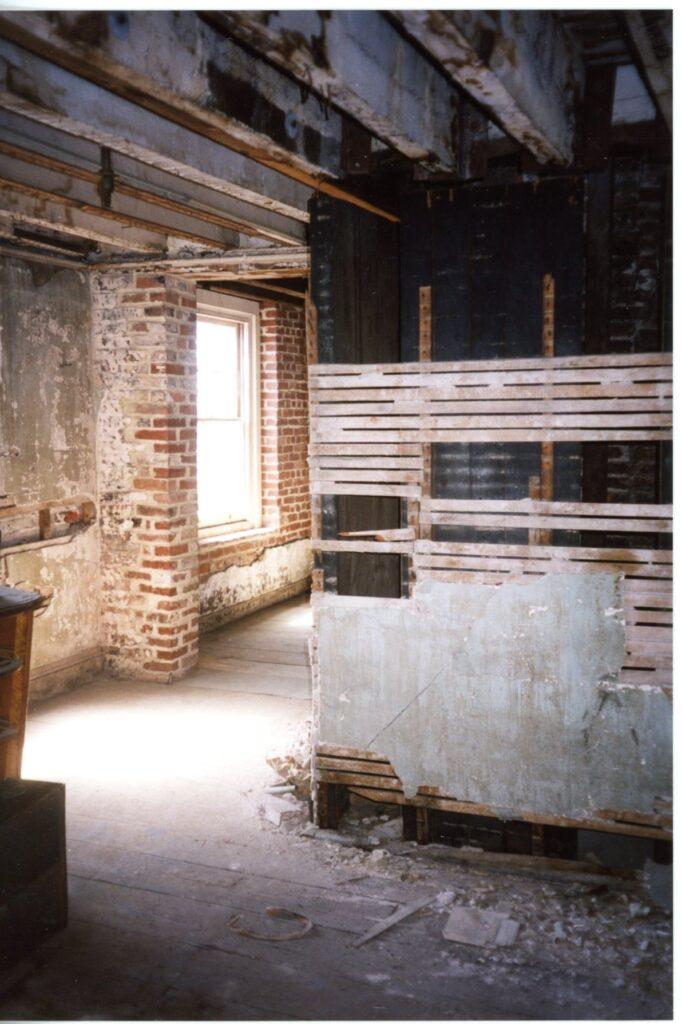

Interiors of Schermerhorn Row. ca. 1985. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive.

In the late 1990s through 2003, the architectural firm Beyer Blinder and Belle (BBB) was commissioned to renovate the Museum’s spaces and galleries within Schermerhorn Row, resulting in its current layout. BBB developed a master plan to organize the various components of the Museum around a new central court located in the core of the block—which is experienced by visitors today in the first floor galleries at 12 Fulton Street—and an escalator providing access to the upper-level Museum spaces, including 21 individual gallery spaces on a total of three floors[4]New Body for a Seaport’s Soul; At Maritime Museum’s Remade Home, Old Walls Talk by Glenn Collins. The New York Times, July 3, 2003..

Schermerhorn Row, 1983. Photographs by Jeff Perkell. South Street Seaport Museum Institutional Archive.

During this renovation of the Row, 19th and early 20th century graffiti was uncovered and preserved, creating an invaluable primary-source to document the historic value of these buildings. Analysis of the graffiti offers a glimpse into the working lives of the people whose labor helped build New York City, conveyed through their own words inscribed on the walls.

The remains of the old hotels and the graffiti are now formally part of the Museum’s accessioned permanent collections. They are preserved like many other types of collections.

More Views of Schermerhorn Row from the Archives

South Street Seaport Museum

By subway: Take the A, C, 2, 3, J, Z, 4, or 5 train to Fulton Street.

By bus: Take the M-15 SBS or M-15 to Fulton Street.

By water: The NYC Ferry, and New York Waterway provide service to Pier 11. The Staten Island Ferry provides services to Whitehall Terminal.

Parking: Parking lots can be found at Front and John Streets, as well as 294 Pearl Street.

References

| ↑1 | Walking Around South Street by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock, 1974, pp. 8-11. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Learn more about the history and care of these historical remnants in the Collections Chronicles blog post “Housekeeping in a 150 year old Hotel.” |

| ↑3 | Creative Time was one of the organizations that emerged out of these conversations thanks to of an informal discussion between three friends: Karin Bacon and Susan Henshaw Jones, who worked in Mayor Lindsay’s administration, and Anita Contini, an actress and dancer, who would become the organization’s first executive director from 1973 to 1986. In an effort to revitalize the South Street Seaport area, they organized a summer arts festival that would bring together two rarely intersecting communities: the artists who lived there and the business people who worked there. Creative Time, A History, by Kriby Gookin. |

| ↑4 | New Body for a Seaport’s Soul; At Maritime Museum’s Remade Home, Old Walls Talk by Glenn Collins. The New York Times, July 3, 2003. |